The Truth About Phosphates in Pool Water

Let us guess. You’re here because you’ve witnessed and maybe even participated in the widespread debate every pool owner encounters at one time or another: Are phosphates in pool water a problem, and do you really have to remove them?

Spoiler alert: The answers are no and no.

Some pool pros and pool chemical sellers will tell you that only by removing phosphates from your pool can you fully and completely control algae growth. You see, phosphates are a nutrient source for algae. The more phosphates in the water, the more yummy food there is for algae to consume, and the faster the algae will grow.

But this is only half the story. Actually, it’s only about a quarter of it. Removing the food source isn’t truly addressing the problem.

Look at it this way. Say you have a vegetable garden in your back yard, and it’s being wrecked by beetles that love to eat those veggies. How are you going to address the problem? By ripping out your garden to remove the beetles’ food source? Of course not. You’re going to use an insecticide to kill the existing beetles, and to keep the beetles that haven’t arrived yet from damaging your garden in the first place.

OK, we admit this isn’t a perfect analogy. But it’s apt because to us, the idea of using a phosphate remover in your pool is just as silly and unnecessary as destroying your entire vegetable garden to get rid of pests.

We decided to put on our researcher caps and do a deep dive into the topic to demonstrate why phosphates in pool water are not where you should be focusing your attention—or spending your money.

This is the ultimate guide to keeping your pool sparkling clean throughout the year that contains everything you need to know about taking care of your pool the right way.

The Condensed Version

Phosphates are not toxic or harmful, and removing them as a remedy to the formation and proliferation of algae is ineffective. Your best bet is to maintain proper chlorine levels, regularly use an algaecide to prevent algae from blooming in your pool, and occasionally shock your pool to give it a really good sanitizing whammy.

This fast-acting, quick-dissolving swimming pool shock kills bacteria, controls algae, and destroys organic contaminants in pools.

If you’d like to stick around to the end, we’re going to explain exactly why this is true. It all starts in the 1940s. But before we go back into phosphate history, let’s take a look at exactly what we’re dealing with here.

What Are Phosphates?

We’re so glad you asked! The quick answer is they’re chemical compounds that contain phosphorus. If you remember any of your high school chemistry, you’ll know this is a naturally occurring, non-metal element. In addition to phosphorus, phosphates contain oxygen and sometimes hydrogen, as well as other chemicals.

For example, when phosphorus is combined with salt, the resulting compound is sodium triphosphate, also called sodium tripolyphosphate, or STPP. This may sound foreign to you, but chances are, you’ve used it before, possibly every day. And this is where we travel back in time to the mid-1940s, with a quick stop in twelfth-century Spain.

A Soapy History

Soaps and detergents used to be made from natural ingredients such as wood ashes and animal fat, or tallow. And you’ve probably heard of Castile soap and know that it’s a vegetable-based cleanser, but you may not know why it’s called that.

Legend has it that vegetable oil-based soap, was created millennia ago in Syria, and then, in the eleventh century, was discovered by Crusaders who brought the “Aleppo soap” back to Spain and Italy. Whether this is actually true has yet to be verified.

What is true is that sometime in the twelfth century, soapmakers began producing olive oil-based soap in the Castile region of Spain. Castile soap eventually came to mean any vegetable oil-based soap.

While soap made from natural ingredients can be good for the environment, it’s not always the most effective cleanser, particularly when it comes to detergency, which is the soap’s ability to dissolve grease. And, as you might’ve guessed, that’s where the word detergent comes from.

Natural soaps were used for centuries until just after World War II, when the soap industry began to develop synthetic detergents that could perform better in areas with hard water, and didn’t rely on fats and oils, which were in high demand. And so began a revolution in laundry rooms across the country, and around the world.

Stick with us. We promise we’re going to get to the phosphates in your pool water.

No More Ring Around the Collar

Synthetic laundry detergents contain a few primary components: a surfactant (a wetting agent that floats dirt off fabric surfaces), a builder, and other ingredients like brighteners and perfumes. We’re going to focus on the builder.

The builder’s function is to soften water and to release hard-to-clean stains and calcium buildup. Because phosphates—in particular, STPP—are especially good at removing calcium deposits, the soap industry began using it as the primary builder in laundry detergents, and eventually in other industrial and domestic cleaning products such as dishwasher detergents.

The first company to create synthetic laundry detergent was Procter & Gamble (P&G) with their brand Dreft®, launched in 1933. They soon found it didn’t clean heavily soiled clothes very well, though, so they marketed it as a gentle detergent for delicate fabrics and baby items, which it continues to be today.

Their next experiment was much more successful. With the addition of phosphates, they created an efficient detergent that cleaned better than any formula that had come before it. The result was Tide, launched in 1946. By 1949, P&G’s production of detergent far exceeded that of soap.

As a result, laundry wasn’t as difficult a chore as it once had been. It was easier to get clothes clean, and with less effort. The laundry detergent industry boomed. Everything seemed peachy keen. That is, until the late 1960s.

Mid-Century Mayhem

By 1959, nearly all the laundry detergents produced in the United States contained builders made up of 30% to 50% phosphate. Other products were also manufactured using phosphates such as household cleaners and dishwasher detergent.

Where does that phosphate end up? In our lakes and streams. Here’s how.

The water that comes out of our taps at home starts out as rain, falls into lakes and reservoirs, and is sent through water treatment plants to be cleaned and sanitized so it’s potable (drinkable) and suitable for things like washing our clothes and dishes.

When we’re done with the water in our homes, it goes down the drains and makes its way to wastewater treatment plants where the waste substances are removed. The water is then pumped out of the plant, and back into our lakes and streams to start the process over again.

Sounds pretty efficient and green, right? The problem is that in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, no one realized that all the phosphates that had been added to detergents and cleaners had the potential to wreak havoc in those natural aquatic environments, or that wastewater treatment methods remove only a small amount of phosphates from water.

Now we get back to phosphate being an ideal food for algae. Just one pound of phosphate can produce 700 pounds of algae. All the phosphate being pumped into lakes, rivers, and streams from wastewater plants created huge algae blooms. By the late 1960s, thousands of lakes and rivers—including the Great Lakes and the Potomac River and its estuary—had been affected.

In fact, as recently as 2014, communities that depend on Lake Erie for their drinking water were contending with algae contamination, although in that case the problem was caused mostly by fertilizer used by farms, and leaky septic systems. The point is, too much algae in our natural water sources continues to be a problem.

How Phosphates Damage the Environment

Ecosystems rely on delicate balances. Prey and predators. Rainfall and plant growth. The presence of food, water, and oxygen, the most basic needs of all living organisms.

In aquatic environments, fish, plants, and numerous other creatures and organisms that live underwater depend on the presence of oxygen in the water. This includes algae. The more algae in the water, the less oxygen there is for the other beings that depend on it, a process called eutrophication. Without oxygen, those creatures begin to die.

Algae stores phosphates to sustain itself. When it dies, algae sinks to the bottom of whatever body of water it’s in, and the phosphate it was retaining is released back into the water to serve as food for remaining algae, and for new growth. The cycle continues and worsens, especially with new phosphate still being introduced from outside sources. This excess of algae is called nutrient pollution, and it continues to be one of the worst types of pollution in our world today.

In addition, the more algae in a source of drinking water, the less clean water there is to drink, so the mammals that depend on a lake or stream will also either begin to die, or they’ll be forced to move in order to find water.

Finally, remember those lakes that act as the source of the water that comes into our homes? When they become polluted with an overgrowth of algae, it has a negative effect on water treatment by clogging intakes, making filtration more expensive, increasing pipe corrosion, and causing taste and odor problems.

The increased effort to make algae-infested water suitable for our use costs money, and that cost gets passed on to us by our water utilities.

Phosphates ending up in our water sources was causing an enormous environmental crisis. Something had to be done.

Fill your pool or hot tub with this hose filter that'll filter your water so you can have a fresh start with water chemistry.

The Detergent Industry Cleans Its Conscience

Starting in 1970, the three major detergent manufacturers in the United States—P&G, Lever Brothers, and Colgate-Palmolive—began a concerted effort to reduce phosphates in the laundry detergents they produced.

However, it wasn’t until the early 1990s that phosphates were completely removed from laundry detergents produced in the U.S. after several states banned phosphate detergents. Numerous countries about the world, most notably in the European Union, have also instituted such bans.

In 2010, several U.S. states also banned dishwasher detergents that use phosphates. In response, manufacturers stopped using phosphates in their dishwasher detergents because it didn’t make sense, nor was it cost effective to produce non-phosphate detergent for some states, and traditional detergent for others.

Phosphates, and the algae that feed on them, continue to be a problem in natural bodies of water. Which brings us to the phosphates in your pool, and why you don’t need to worry about them.

Phosphates in Pool Water Aren’t Going Anywhere

As we’ve said, phosphates as a food source for algae have been, and still are, a problem in our natural bodies of water, and our sources of drinking water.

We don’t need to tell you that your pool is neither of those things.

We also don’t need to tell you that you’re not going to be draining your pool very often, which means you won’t have thousands of gallons of phosphate-laden water pouring into your municipal water system on a regular basis, and eventually making its way to your local lakes and streams.

Not only that, we’re pretty sure that if you’re a conscientious pool owner, you’re using chlorine or some other kind of sanitizer in your pool, which means you’re already making the water inhospitable to algae.

And if you’re using an algaecide on top of that (which we highly recommend you do), you’re decreasing the likelihood of developing pool algae to almost nil.

A copper-free algaecide to help prevent your pool from turning green.

So why on earth would you spend more money on yet another chemical to stop feeding the thing you’re already killing and preventing? It just doesn’t make any sense. In fact, aside from expense and futility, we discovered a couple of reasons why you’ll actually want to avoid using phosphate removers.

Phosphate Removers Can Be Toxic

Since we’ve been talking about the environment, let’s look at phosphate remover’s effects there first.

Some of the most popular phosphate removers have an active ingredient—the substance that actually works on the phosphates—called lanthanum. It’s a soft metal element that’s classified as a rare earth element despite the fact that it’s almost three times more abundant than lead.

In 2016, the scientific journal Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety published an article titled “Aquatic Ecotoxicity of Lanthanum – A Review and an Attempt to Derive Water and Sediment Quality Criteria,” which revealed some interesting findings about lanthanum.

First, lanthanum is classified as “moderately toxic,” which seems to be borne out in this study. Remember that while phosphates are indeed a food source for algae, they are not toxic. The study showed that freshwater crustaceans were particularly sensitive to lanthanum. The study goes on to say (emphasis and parentheses ours):

“As with other metals, the availability of lanthanum is strongly influenced by pH and by the presence of other cations in the environment. It can be accumulated by organisms, it can interfere with cellular functions and it adsorbs to (is absorbed by) particles.

More study is required to fully determine the level of its toxicity to organisms, including humans, but based on these preliminary findings, lanthanum doesn’t sound like something we’d want to pour into our pools.

Phosphate Removers Can Negate the Effects of Sequestrants

Let’s say you have a high level of copper or iron in your pool water. Maybe you get your water from a well. Left unchecked, a high copper level will eventually turn your pool green, while iron will give it a lovely rusty brown color. Yuck.

So you break out the metal sequestrant to bind with the copper or iron and keep it it from oxidizing or rusting, which will prevent your pool water from turning those ugly colors.

Here’s the thing. The most effective metal sequestrants are phosphate-based. If you have metal in your pool, and you use a phosphate-based sequestrant, and then use a phosphate remover, you’re negating the effects of the sequestrant.

You’ll lower the phosphate level, but have little to no success counteracting the effects of the metal, which means you’ll be wasting money on two fronts.

What About Salt Water Chlorinators?

In addition to the general debate about phosphates, you may have seen some websites mention that phosphates can cause salt water chlorinators to malfunction. Interestingly, at least one article that says this is a problem is published on a site that contains advertising by one of the main companies that produces and sells phosphate remover.

Aside from any potential biases, though, the fact is no scientific studies have been done, which means no verifiable, objective data exists to support this theory.

Some pool owners may claim that phosphates are to blame for their chlorinators being unable to produce appropriate amounts of chlorine. But what if it’s the other way around? What if the pool contains more phosphates because the chlorinator is not producing enough chlorine in the first place to kill the contaminants and organisms that produce phosphates?

We don’t know for sure because, again, no scientific studies of this possible phenomenon exist, and we don’t have access to a large enough number of pools to test it ourselves.

So until we see hard evidence, we’re going to stick with our advice that a phosphate remover is unnecessary, even in a salt water pool.

What to do About Phosphates in a Salt Water Pool

If you have a salt water pool, your phosphate levels are high, and your chlorinator isn’t producing enough chlorine, the first thing to check is that your chlorinator is built to handle the size of your pool.

Even if it is, you may still need to supplement with regular chlorine once in a while, depending on where you live, and what the environmental conditions are like there.

And finally, are you shocking your pool often enough to kill phosphate-producing organisms? Maybe you need another shock or two per month, and perhaps even more when it rains.

Examine all the possible factors that may be contributing to low chlorine levels before jumping to the conclusion that you need to douse your pool with potentially toxic phosphate remover.

This salt water generator (or salt water chlorinator) has a high/low salt and temperature indicators to help protect your equipment. And the self-cleaning salt cell makes regular maintenance easy. Check out their models for both inground and above ground pools.

The Verdict: You Really, Truly Do Not Need a Phosphate Remover

If you’ve stuck with us to the end, hooray! Now we can feel good about all that time we spent reading scientific journal articles, and boning up on the history of detergent. (We are so ready to kick butt on Jeopardy!)

But we feel even better about providing you with information that will help you save money, and will put your mind at ease about how you maintain your pool.

Focus on the three most important algae fighters—sanitizer, algaecide, and the occasional pool shock—and your pool will be just fine.

Happy (and less expensive) Swimming!

3 Ways We Can Help With Your Pool

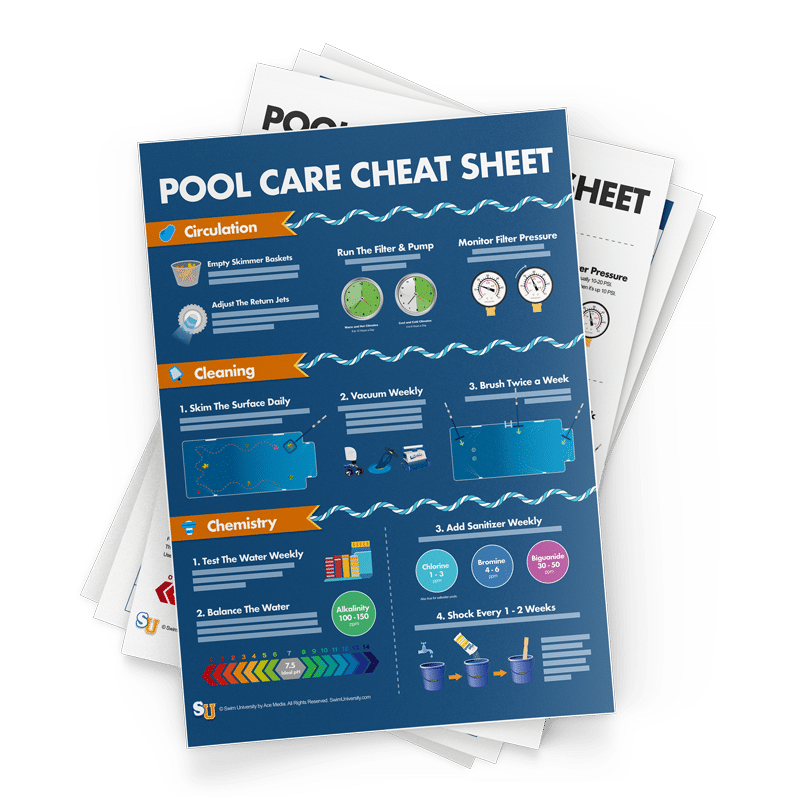

- Pool Care Cheat Sheets (Free): Easy-to-use downloadable guides to help you keep track of taking care of your pool this year.

- The Pool Care Handbook: An illustrated guide to DIY pool care, including water chemistry, maintenance, troubleshooting, and more.

- The Pool Care Video Course: You’ll get 30+ step-by-step videos and a downloadable guide with everything you need to know about pool maintenance.